MATH 119: Calculus 2¶

Multivariable functions¶

Definition

- A multivariable function accepts more than one independent variable, e.g., .

The signature of multivariable functions is indicated in the form [identifier]: [input type] → [return type]. Where is the number of inputs:

Example

The following function is in the form and maps two variables into one called via function .

Sketching multivariable functions¶

Definition

- In a scalar field, each point in space is assigned a number. For example, topography or altitude maps are scalar fields.

- A level curve is a slice of a three-dimensional graph by setting to a general variable . It is effectively a series of contour plots set in a three-dimensional plane.

- A contour plot is a graph obtained by substituting a constant for in a level curve.

Please see level set and contour line for example images.

In order to create a sketch for a multivariable function, this site does not have enough pictures so you should watch a YouTube video.

Example

For the function :

For each :

- Set equal to the variable and substitute it into the equation

- Sketch a two-dimensional graph with constant values of (e.g., ) using the other two variables as axes

Combine the three contour plots in a three-dimensional plane to form the full sketch.

A hyperbola is formed when the difference between two points is constant. Where is the x-intercept:

If is negative, the hyperbola is is bounded by functions of , instead.

Limits of two-variable functions¶

A function is continuous at if and only if all possible lines through have the same limit. Or, where is a constant:

In practice, this means that if any two paths result in different limits, the limit is undefined. Substituting or or are common solutions.

Example

For the function :

Along :

Along :

Therefore the limit does not exist.

Partial derivatives¶

Partial derivatives have multiple different symbols that all mean the same thing:

For two-input-variable equations, setting one of the input variables to a constant will return the derivative of the slice at that constant.

By definition, the partial derivative of with respect to (in the x-direction) at point is:

Effectively:

- if finding , should be treated as constant.

- if finding , should be treated as constant.

Example

With the function :

Higher order derivatives¶

Definition

- wrt. is short for "with respect to".

Derivatives of different variables can be combined:

The order of the variables matter: is the derivative of f wrt. x and then wrt. y.

Clairaut's theorem states that if , and all exist near and is continuous at , and exists.

Warning

In multivariable calculus, differentiability does not imply continuity.

Linear approximations¶

A tangent plane represents all possible partial derivatives at a point of a function.

For two-dimensional functions, the differential could be used to extrapolate points ahead or behind a point on a curve.

The equations of the two unit direction vectors in and can be used to find the normal of the tangent plane:

Therefore, the general expression of a plane is equivalent to:

Proof

The general formula for a plane is .

If is constant such that :

which must represent in the x-direction as an equation in the form . It follows that . A similar concept exists for .

If both and are constant:

where must be the -point.

Usually, functions can be approximated via the tangent at .

Warning

Approximations are less accurate the stronger the curve and the farther the point is away from . A greater indicates a stronger curve.

Example

Given the function , can be linearly approximated.

Differentials¶

Linear approximations can be used with the help of differentials. Please see MATH 117#Differentials for more information.

can be assumed to be equivalent to .

Alternatively, it can be expanded in Leibniz notation in the form of a total differential:

Proof

The general formula for a plane in three dimensions can be expressed as a tangent plane if the differential is small enough:

As , , and , it can be assumed that .

Related rates¶

Please see SL Math - Analysis and Approaches 1 for more information.

Example

For the gas law , if increases by 1% and increases by 3%:

Parametric curves¶

Because of the existence of the parameter , these expressions have some advantages over scalar equations:

- the direction of and can be determined as increases, and

- the rate of change of and relative to as well as each other is clearer

The derivative of a parametric function is equal to the vector sum of the derivative of its components:

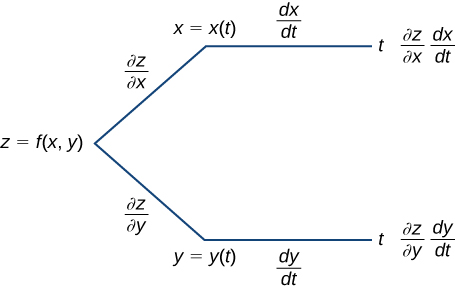

Sometimes, the chain rule for multivariable functions creates a new branch in a tree for each independent variable.

For two-variable functions, if :

Sample tree diagram:

(Source: LibreTexts)

(Source: LibreTexts)

Example

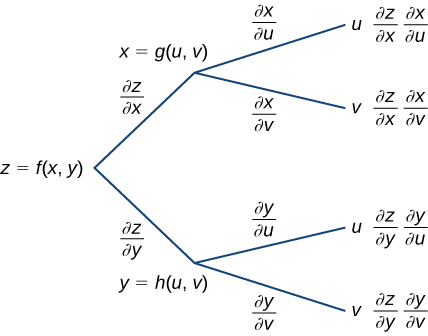

This can be extended for multiple functions — for the function , where and :

(Source: LibreTexts)

(Source: LibreTexts)

Determining the partial derivatives with respect to or can be done by only following the branches that end with those terms.

Warning

If the function only depends on one variable, is used. Multivariable functions must use to treat the other variables as constant.

Gradient vectors¶

The gradient vector is the vector of the partial derivatives of a function with respect to its independent variables. For :

This allows for the the following replacements to appear more like single-variable calculus. Where is a desired point, is the initial point, and all vector multiplications are dot products:

Linear approximations are simplified to:

The chain rule is also simplified to:

A directional derivative is any of the infinite derivatives at a certain point with the length of a unit vector. Specifically, in the unit vector direction at point :

This reduces down by taking only as variable to:

Cartesian and polar coordinates can be easily converted between:

Optimisation¶

Local maxima / minima exist at points where all points in a disk-like area around it do not pass that point. Practically, they must have .

Critical points are any point at which . A critical point that is not a local extrema is a saddle point.

Local maxima tend to be concave down while local minima are concave up. This can be determined via the second derivative test. For the critical point of :

- Calculate

- If it greater than zero, the point is an extremum a. If , the point is a maximum — otherwise it is a minimum

- If it is less than zero, it is a saddle point — otherwise the test is inconclusive and you must use your eyeballs

Optimisation with constraints¶

If there is a limitation in optimising for in the form , new critical points can be found by setting them equal to each other, where is the Lagrange multiplier that determines the rate of increase of with respect to :

The largest/smallest values of from the critical points return the maxima/minima. If possible, should also be tested afterward.

Example

If , , and should be maximised:

Example

If and the constraint must be satisfied:

Example

If and the constraint must be satisfied:

Alternatively, trigonometric substitution may be used to solve the system parametrically.

Warning

Terms cannot be directly cancelled out in case they are zero.

This applies equally to higher dimensions and constraints by adding a new term for each constraint. Given with constraints and :

Absolute extrema¶

- If end points exist, those should be added

- If no endpoints exist and the limits go to , there are no absolute extrema

Double integration¶

In a nutshell, double integration is done by taking infinitely small lines then finding the area under those lines to form a volume.

For a surface formed by vectors and :

If the function is continuous and bounds do not depend on variables, the order of integration doesn't matter.

Example

For and :

If the function is the product of two functions of separate variables, i.e., if :

Volume betweeen two functions¶

The result of the bound variable should be integrated first. For functions of :

Functions can also be replaced to be bounded by the other if necessary.

Example

For bounded by and :

Example

For bounded by , , and :

Double polar integrals¶

The differential elements can be directly replaced:

In general, the radius should be the inner integral, and functions converted from Cartesian to polar forms.

Change of variables¶

The Jacobian is the proportion of change in the differentials between different coordinate systems.

The Jacobian can be treated as a fraction — it may be easier to determine the reciprocal of the Jacobian and then reciprocal it again.

When converting between two systems, the absolute value of the Jacobian should be incorporated.

Example

The Jacobian of the polar coordinate system relative to the Cartesian coordinate system is . Therefore, .

If , , and in the domain of and :

- Pick a good transformation that simplifies the domain and/or the function.

- Compute the Jacobian

- Determine bounds (domain)

- Integrate with the formula

If the Jacobian contains and/or terms:

- they can be substituted into the integral directly, praying that the terms all cancel out

- or and can be written in terms of and and then all substituted

Example

For the volume within bounded by :

By graphical inspection, the bounds can be determined to be .

Let . Let . The bounds change to .

Applications of multiple integrals¶

The area enclosed within bounds is the volume with a height of 1.

Example

For the area between and :

POI:

Example

For the area of in the region :

For ellipses of this form, a direct substitution to and is fastest.

Let and .

Thus .

Let . Radius is 1 by inspection.

The average value of the function over a region , where is the area of the region:

Example

The average value of over :

The total "amount" of within a region, if describes the density at point :

Example

The total of with density :

Let . Thus .

Let . Thus .

Triple integration¶

Much like double integrals:

The volume within bounds is the integral of 1:

The average value within a volume is:

Example

For the volume within and :

The points intersect the axes and each other to create the bounds .

The average value is:

The total quantity if represents density is:

Cylindrical coordinates¶

Cylindrical coordinates are effectively polar coordinates with a height.

The Jacobian is still .

Example

For the volume under , outside , and above the plane:

Spherical coordinates¶

Where is the direct distance from the point to the origin, is the angle to the x-axis in the xy-plane (), and is the angle to the z-axis, top to bottom ():

The Jacobian is .

Example

The mass inside the sphere with density :

It is clear that . Thus:

Approximation and interpolation¶

Each of these finds roots, so a rooted equation is needed.

Example

To find an where , the root of should be found.

Bisection¶

- Select two points that are guaranteed to enclose the point

- Select an arbitrary and check if it is greater than or less than zero

- Slice the remaining section in half in the correct direction

Newton's method¶

The below formula can be repeated after plugging in an arbitrary value.

Warning

If Newton's method converges to the wrong root, bisection is necessary to brute force the result.

Polynomial interpolation¶

Where are the th differences between the points:

Taylor polynomials¶

The th order Taylor polynomial centred at is:

Maclaurin's theorem states that if some function for all :

Example

If and , ... TODO

The desired function being the th degree Maclaurin polynomial implies that is the th degree polynomial for .

Therefore, if you have the Maclaurin polynomial where is the th order Taylor polynomial:

- for

- for

The integration constant can be found by substituting as and solving.

For , where is the Maclaurin polynomial for of order , is the th order polynomial for .

Taylor inequalities¶

The triangle inequality for integrals applies itself many times over the infinite sum.

The Taylor remainder is the error between a Taylor polynomial and its actual value. Where is an arbitrary value chosen as the upper bound of the difference of the first derivative between and :

An approximation correct to decimal places requires that .

Warning

should be as small as possible. When rounding, round down for the lower bound, and round up for the upper bound.

Integral approximation¶

The upper and lower bounds of a Taylor polynomial are clearly . Integrating them separately reveals creates bounds for the integral.

Infinite series¶

The th partial sum of a sequence is used to determine divergence.

A sum converges to if the sum eventually ends up there. Otherwise, if the limit is infinity or does not exist, it diverges.

Divergence test¶

By the divergence test, if the limit of each term never reaches zero, the sum diverges.

Geometric series¶

The th partial sum of a geometric series is equal to:

To simply test for convergence:

- If , .

- Otherwise, it diverges by the test for divergence.

Integral test¶

If is continuous, decreasing, and positive on some :

p-series test¶

For all , a series of the form

converges if and only if .

Comparison test¶

For two series and where all terms are positive, if for all , either both converge or both diverge.

The limit comparison test has the same requirements, but if such that , either both converge or both diverge.

Ratio tests¶

The ratio test is applicable if the exists or is infinity:

- implies the function converges absolutely

- implies the function diverges

- is inconclusive

It is useful if a constant is raised to the power of or if a factorial is present.

The root test has the same analysis but with a different limit:

It is useful for functions of the form .

Alternating series¶

If the absolute value of all terms continuously decreases and , the alternating function converges.

The alternating series estimation theorem places an upper bound on the error of a partial sum. If the series passes the alternate series test, is the th partial sum, is the sum of the series, and is the th term:

Conditional convergence¶

converges absolutely only if converges.

An absolutely converging series also has its regular form converge.

A series converges conditionally if it converges but not absolutely. This indicates that it is possible for all to rearrange to cause it to converge to .

Power series¶

A power series centred at is an infinitely long polynomial.

If there are multiple identified domains of convergence, the endpoints must be tested separately to get the interval of convergence. The radius of convergence is the amplitude of the interval, regardless of inclusion/exclusion.

For a power series of radius , regardless if it is differentiated, integrated, multiplied (by non-zero), the radius remains .

Warning

The interval may change.

Adding functions with different radii results in a radius roughly near the smaller interval of convergence.

The binomial series is the infinite expansion of with radius 1.

Big O notation¶

A function is of order as if for all near . This is written as big O:

The inner function only dictates how it grows, discarding any constant terms.

Example

As , as well as and . Thus for all .

However, only as by the definition.

Example

As , as .

If and as :

-

, where

q=min(m,n)

With Taylor series, big O is the remainder.

The limit of big O is the behaviour of .

Example